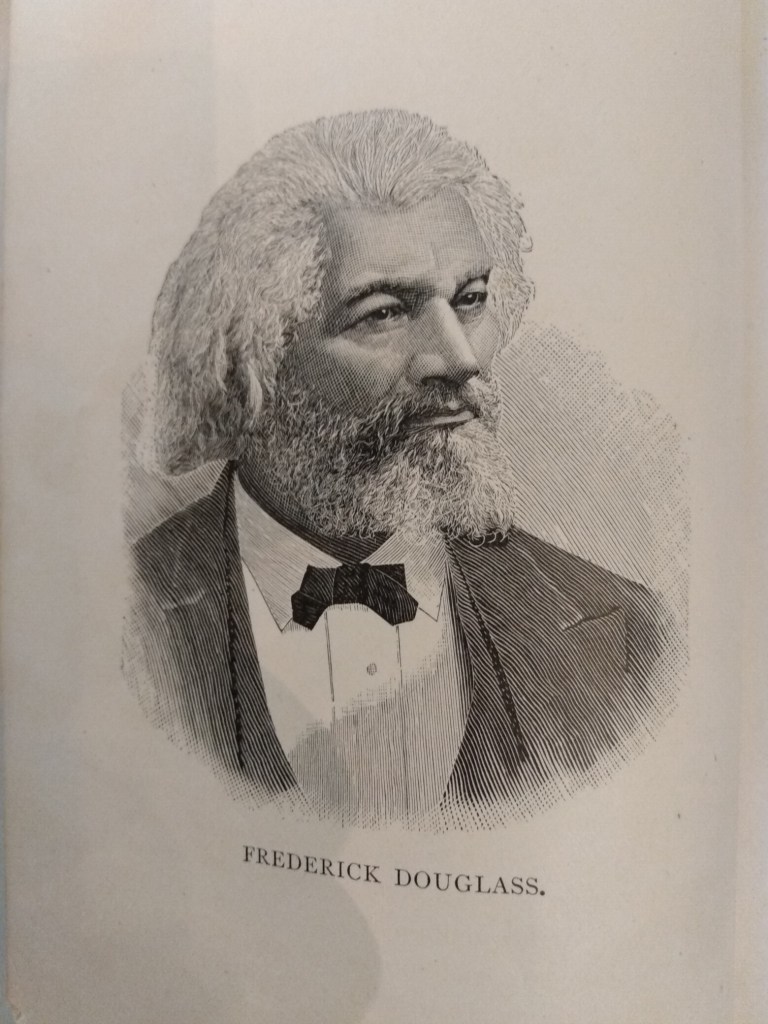

1. HON. FREDERICK DOUGLASS, LL. D.

Magnetic Orator – Anti-slavery Editor – Marshal of the District of Columbia – Recorder of Deeds of the District of Columbia – First Citizen of America – Eminent Patriot and Distinguished Republican.

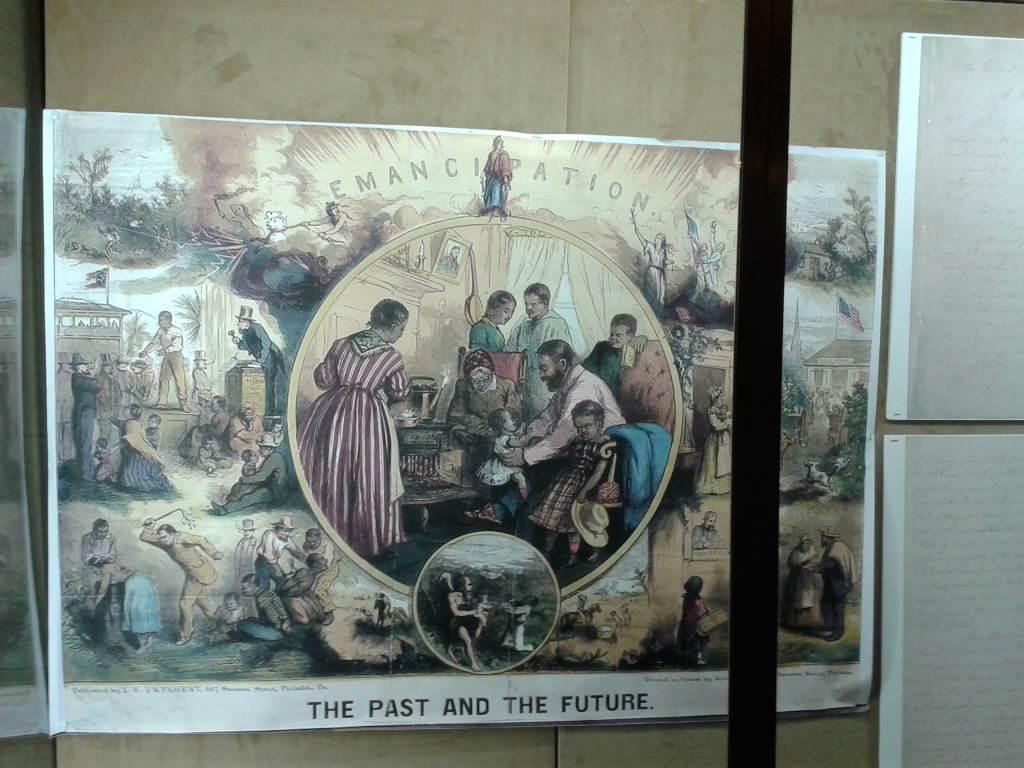

Who can write the life of this great man and do him justice? His life is an epitome of the efforts of a noble soul to be what God intended, despite the laws, customs and prejudices. That such a soul as Douglass’ could be found with the galling bonds of slavery is the blackest spot in the realm of thought and fact in the whole history of this government. But such a man as he would not remain in slavery, could not do so. Aye! it was impossible to fetter him and keep him there. He was a man. He was not going to remain bound while his legs could carry him off, and, as he facetiously remarked, he prayed for freedom, but when he made his legs pray, then he got free. He shows himself a man of works as well as faith. And these go together. But eulogy is wasted on such a man. His life speaks, and, when he is dead, his orations will keep his memory fresh, and his name will stand side by side with Webster, Sumner and Clay.

Frederick Douglass was born about the year 1817, in Tuckahoe, a barren little district upon the eastern shore of Maryland, best known for the wretchedness, poverty, slovenliness and dissipation of its inhabitants. Of his mother he knew very little, having seen her only a few times in his life, as she was employed on a plantation some distance from the place where he was raised. His master was supposed to be his father.

No man perhaps has had a more varied experience than the subject of this sketch. During his early childhood he was beaten and starved, often fighting with the dogs for the bones that were thrown to them. As he grew older and could work he was given very little to eat, overworked and much beaten. As the boy grew older still, and realized the misery and horror of his surroundings, his very soul revolted, and a determination was formed to be free or to die attempting it.

At the age of ten years he was sent to Baltimore to Mrs. Sophia Auld, as a house servant. She became very much interested in him, and immediately began teaching him his letters. He was very apt, and was soon able to read. The husband of his mistress, finding it out, was very angry and put a stop to it.

This prohibition served only to check the instruction from his mistress, but had no effect on the ambition, the craving for more light, that was within the boy, and the more obstacles he met with the stronger became his determination to overcome them. He carried his spelling book in his bosom and would snatch a minute now and then to pursue his studies. The first money he made he invested in a “Columbian Orator.” In this work he read “The Fanaticism of Liberty” and the “Declaration of Independence.” After reading this book he realized that there was a better life waiting for him, if he would take it, and so he ran away.

He settled in New Bedford with his wife, who, a free woman in the South, being engaged to Douglass before his escape, followed him to New York, where they were married. She was a worthy, affectionate, industrious and invaluable helpmate to the great Douglass. She ever stood side by side with him in all his struggles to establish a home, helped him and encouraged him while he climbed the ladder of knowledge and fame, together with him offered the hand of welcome and a shelter to all who were fortunate enough to escape from bondage and reach their hospitable shelter; and never, while loving mention is made of Frederick Douglass, may the name of his wife “Anna” be forgotten.

In New Bedford he sawed wood, dug cellars, shoveled coal, and did any other work by which he could turn an honest penny, having the incentive that he was working for himself and his family, and that there was no master waiting for his wages. Here several of the children were born.

He began to read the Liberator, for which he subscribed, and other papers, and works of the best authors. He was charmed by Scott’s “Lady of the Lake,” and reading it he adopted the name of “Frederick Douglass.” He began to take an interest in all public matters, often speaking at the gatherings among the colored people. In 1841 he addressed a large convention at Nantucket. After this he was employed as an agent of the American Antislavery Society, which really marks the beginning of his grand struggle for the freedom and elevation of his race. He lectured all through the North, notwithstanding he was in constant danger of being recaptured and sent to the far South as a slave. After a time it was deemed best that he should for a while go to England. Here he met a cordial welcome. John Bright established him in his house, and thus he was brought in contact with the best minds and made acquainted with some of England’s most distinguished men. His relation of the wrongs and sufferings of his enslaved brethren excited their deepest sympathy; and their admiration for his ability was so profound, their wonder so great, that there should be any fear of such a man being returned to slavery, that they immediately subscribed the amount necessary to purchase his freedom, made him a present of his manumission papers, and sent him home to tell his people that

Slaves cannot breathe in England;

If their lungs receive our air, that moment they are free;

They touch our country, and their shackles fall.

Returning to America he settled in Rochester, New York, and established a paper called the North Star, afterwards changed to Fred Douglass’ Paper, also Douglass’ Monthly. These were all published in his own office, and two of his sons were the principal assistants in setting up the work, and attending to the business generally.

There has been a great deal of speculation as to what connection Frederick Douglass had with the John Brown raid. The two great men met, and Brown became acquainted with Douglass’ history. They became fast friends.

They were singularly adapted to each other as co – workers, both being deeply imbued with the belief that it was their duty to devote their lives and means to the cause of emancipation. They lived frugally at home that they might have the more to give. Their families caught their inspiration, and their lives were all influenced by the one motive – power – the cause of freedom. Many men and women who successfully escaped into Canada, and thence to other places, will tell how, after they had been well fed, nourished and made comfortable by the mother, one of Fred Douglass’ boys had carried them across the line and seen them to a place of safety. When other boys were enjoying all the comforts and pleasures their parents could provide for them, Douglass’ sons were made to feel that there was only one path for them to walk in until the great end for which they were working had been attained.

Brown’s first plan was to run slaves off, and in this Douglass heartily joined him; but when he found Brown had decided to attempt the capture of Harper’s Ferry, he went to him at Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, a short time before the raid, and used every argument he could to induce him to change his plans. Brown had enlisted a body of men to accompany him who felt as he felt, that their lives were nothing as weighed against the lives and liberties of so many who were suffering in bondage. His arms and ammunition were ready, his plans were all laid, and to Douglass’ argument he answered: “If we attack Harper’s Ferry, as we have now arranged, the country will be aroused, and the Negroes will see the way clear to liberation. We’ll hold the citizens of the town as hostages, and so holding them can dictate our terms. You, Douglass, should be one of the first to go with us.”

“No, no,” replied the latter, “I can’t agree with you and will not go with you – your attempt can only result in utter ruin to you, and to all those who take part in it, without giving any substantial aid to the men in slavery. Let us rather go on with our first plan of the ‘Underground Railroad’ by which slaves may be run off to the free states. By that means practical results can be obtained. From insurrection nothing can be expected but imprisonment and death.”

“If you think so,” replied Brown, “it is, of course, best that we should part.” He held out his hand. Douglass grasped it. “Goodbye! God bless you!” they exclaimed, almost in the same breath, and then parting forever, were soon lost to each other in the darkness.

It was soon discovered that Douglass and Brown were in sympathy, and that Douglass, besides harboring Brown, had furnished him money to defray expenses, and thus making his safety a matter of great doubt. His friends advised him to leave the country for awhile. They were willing to stand by him, even to fight for him, but felt that it would be wiser to avoid the danger if possible. After much hesitation he was induced to abide by their advice, and the result proved the wisdom of his having done so. He went first to Canada and from there to England. Only a short time after his departure a requisition for his arrest was made by Governor Wise of Virgina. The requisition read as follows:

(Confidential.)

RICHMOND VIRGINIA, November 13, 1859.

To His Excellency, James Buchanan, President of the United States, and to the Honorable Postmaster-General of the United States-

GENTLEMEN: – I have information such as has caused me, upon proper affidavits, to make requisition upon the Executive of Michigan for the delivery up of the person of Frederick Douglass, a Negro man, supposed now to be in Michigan, charged with murder, robbery and inciting servile insurrection in the State of Virginia. My agents for the arrest and reclamation of the person so charged are Benjamin M. Morris and William N. Kelly. The latter has the requisition and will wait on you to the end of obtaining nominal authority as post office agents. They need to be very secretive in this matter, and some pretext of traveling through the dangerous section for the execution of the laws in this behalf, and some protection against obtrusive, unruly or lawless violence. If it be proper so to do, will the Postmaster-General be pleased to give Mr. Kelly for each of these men a permit and authority to act as detectives for the post office department without pay, but to pass and repass without question, delay or hindrance?

Respectfully submitted by your

Obedient Servant,

HENRY A. WISE.

Mr. Douglass did not feel it necessary to hasten his return on account of this interesting document, and so remained abroad till it was safe for him to come home. This adventure did not in the least dampen his ardor in the great cause. Wherever and whenever he could do or say anything for it, he never failed to do so. When the first gun was fired at Sumter, he was among the foremost to insist upon the enrollment of colored soldiers. In 1863 he, with others, succeeded in raising two regiments of colored troops, which were known as Massachusetts regiments. Two of his sons were among the first to enlist. His next move was to obtain the same pay for them that the white soldiers received, and to have them exchanged as prisoners of war; in fact, that there should be no difference made between them and other soldiers. His work did not end with the war. He recognized the fact that a new life had begun for the former slaves; that a great work was to be done for them and with them, and he was ever to be found in the foremost ranks of those who were willing to put their shoulders to the wheel. His means, as well as his time, he largely gave to the cause. He was one of the most indefatigable workers for the passage of the amendments to the Constitution, granting the same rights to all classes of citizens, regardless of race and color. He attended the “Loyalists’ Convention,” held in Philadelphia, in 1867, being elected a delegate from Rochester. Some feared his presence would do more harm than good, knowing how radical he was; but he felt that it was his duty to go, and nothing could change him. It has been conceded that it was due principally to his persistence work in that convention, that resolutions favoring universal suffrage were passed. A little incident in connection with this convention shows the value of his work in that meeting, by disclosing the feeling of the men he had to deal with. As the members assembled proceeded to fall in line, on their way to the place of the meeting, everyone seemed to avoid walking beside a colored delegate. As soon as Theodore Tilton noticed it, he stepped to Douglass’ side, and arm in arm they entered the chamber. This act has made them lifelong friends, and these two are both brotherly in their devoted friendship. In Mr. Douglass’ recent visit to France, he met Mr. Tilton, who resides in Paris, and had a glorious time.

He established the New National Era at Washington, D. C., in 1870. This paper was edited and published principally by him and his sons, and devoted to the cause of the race and the Republican party. In 1872 he took his family to reside in the District of Columbia. In 1871 President Grant appointed him to the Territorial Legislature of the District of Columbia. In 1872 he was chosen one of the Presidential electors-at-large for the State of New York, and was the elector selected to deliver a certified statement of the votes to the president of the Senate.

He was appointed to accompany the commissioners on their trip to Santo Domingo, pending the consideration of the annexation of that island to the United States. President Grant in January, 1877, appointed him a police commissioner for the District of Columbia. In March of the same year President Hayes commissioned him United States marshal for the District of Columbia. President Garfield, in 1881, appointed him recorder of deeds for the District of Columbia. This last position he held till about May, 1886, nearly a year and a half after the ascendancy to the national administration of the Democratic party.

No man has begun where Frederick Douglass did and attained to the same giddy heights of fame. Born in a mere hovel, a creature of accident, with no mother to cherish and nurture him, no kindly hand to point out the good worthy of emulation and the evil to be shunned, no teacher to make smooth the rough and thorny paths leading to knowledge. His only compass was an abiding faith in God, and an innate consciousness of his own ability and power of perseverance.

Harriet Beecher Stowe, in her book entitled ‘Men of Our Times,’ says: “Frederick Douglass had as far to climb to get to the spot where the poorest white boy is born, as that white boy has to climb to be President of the nation, and take rank with kings and judges of the earth.” Again, in the Senate of the United States, in a recent important case under consideration, the following statement formed part of a resolution submitted by that body in reply to the President of the United States: “Without doubt Frederick Douglass is the most distinguished representative of the colored race, not only in this country, but in the world.” To-day he stands the acknowledged peer in intellect, culture and refinement of the greatest men of our age, or any age; in this country, or any country. His name has never been written on the register of any school or college, yet it will ever be written on the pages of all future history, wherever the names of the ablest men of our times appear, side by side with those of the more favored race. His relations with such men as John G. Whittier, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Wendell Phillips, William Loyd Garrison; and such women as Lydia Maria Child, Grace Greenwood, and Harriet Beecher Stowe, have ever been cordial and pleasant. Some men who never graduate from a college have more sense in five minutes than many a conceited graduate who has all his knowledge duly accredited by a sheepskin, but is not the real possessor of an education. The trustees of Howard University honored themselves and their institution, more than they did Mr. Douglass, when they conferred upon him the title of LL. D., and when also they gave him a seat in their board.

Mr. Douglass in ‘His Life,’ written by himself, gives the following account of his visit to his old home:

The first of these events occurred four years ago, when, after a period of more than forty years, I visited and had an interview with Captain Thomas Auld at St. Michaels, Talbot county, Maryland. It will be remembered by those who have followed the thread of my story that St. Michaels was at one time the place of my home and the scene of some of my saddest experiences of slave life, and that I left there, or rather was compelled to leave there, because it was believed that I had written passes for several slaves to enable them to escape from slavery, and that prominent slaveholders in that neighborhood had, for this alleged offense, threatened to shoot me on sight, and to prevent the execution of this threat my master had sent me to Baltimore.

My return, therefore, to this place in peace, among the same people, was strange enough in itself; but that I should, when there, be formally invited by Captain Thomas Auld, then over eighty years old, to come to the side of his dying bed, evidently with a view to a friendly talk over our past relations, was a fact still more strange, and one which, until its occurrence, I could never have thought possible. To me Captain Auld had sustained the relation of master – a relation which I had held in extreme abhorrence, and which for forty years I had denounced in all bitterness of spirit and fierceness of speech. He had struck down my personality, had subjected me to his will, made property of my body and soul, reduced me to a chattel, hired me out to a noted slave breaker to be worked like a beast and flogged into submission; he had taken my hard earnings, sent me to prison, offered me for sale, broken up my Sunday – school, forbidden me to teach my fellow – slaves to read on pain of nine and thirty lashes on my bare back; he had sold my body to his brother Hugh and pocketed the price of my flesh and blood without any apparent disturbance of his conscience. I, on my part, had traveled through the length and breadth of this country and of England, holding up this conduct of his, in common with that of other slaveholders, to the reprobation of all men who would listen to my words. I had made his name and his deeds familiar to the world by my writings in four different languages; yet here we were, after four decades, once more face to face – he on his bed, aged and tremulous, drawing near the sunset of life, and I, his former slave, United States marshal of the District of Columbia, holding his hand and in friendly conversation with him in his sort of final settlement of past differences preparatory to his stepping into his grave, where all distinctions are at an end, and where the great and the small, the slave and his master, are reduced to the same level. Had I been asked in the days of slavery to visit this man, I should have regarded the invitation as one to put fetters on my ankles and handcuffs on my wrists. It would have been an invitation to the auction block and the slave whip. I had no business with this man under the old regime but to keep out of his way. But now that slavery was destroyed, and the slave and the master stood upon equal ground, I was not only willing to meet him but was very glad to do so. The conditions were favorable for remembrance of all his good deeds and generous extenuation of all his evil ones. He was to me no longer a slaveholder either in fact or in spirit, and I regarded him as I did myself, a victim of the circumstances of birth, education, law and custom.

Our courses had been determined for us, not by us. We had both been flung, by powers that did not ask our consent, upon a mighty current of life, which we could neither resist nor control. By this current he was a master, and I a slave; but now our lives were verging towards the point where differences disappeared, where even the constancy of hate breaks down, where the clouds of pride, passion and selfishness vanish before the brightness of Infinite light. At such a time and in such a place, when man is about closing his eyes on this world and ready to step into the eternal unknown, no word of reproach or bitterness should reach him or fall from his lips; and on this occasion there was to this rule no transgression on either side.

As this visit to Captain Auld had been made the subject of mirth by heartless triflers, and regretted as a weakening of my lifelong testimony against slavery by serious minded men, and as the report of it, published in the papers immediately after it occurred, was in some respects defective and colored, it may be proper to state exactly what was said and done at this interview.

It should in the first place be understood that I did not go to St. Michaels upon Captain Auld’s invitation, but upon that of my colored friend, Charles Caldwell; but when once there, Captain Auld sent Mr. Green, a man in constant attendance upon him during his sickness, to tell me that he would be very glad to see me, and wished me to accompany Green to his house, with which request I complied. On reaching the house I was met by Mr. William H. Bruff, a son-in-law of Captain Auld’s, and Mrs. Louisa Bruff, his daughter and was conducted by them immediately to the bedroom of Captain Auld. We addressed each other simultaneously, he calling me “Marshall Douglass,” and I, as I had always called him, “Captain Auld.” Hearing myself called by him “Marshall Douglass,” I instantly broke up the formal nature of the meeting by saying, “Not MARSHALL, but Frederick to you as formerly.” We shook hands cordially, and in the act of doing so he, having been long stricken with palsy, shed tears as men thus afflicted will do when excited by any deep emotion. The sight of him, the changes which time had wrought in him, his tremulous hands constantly in motion, and all the circumstances of his condition affected me deeply, and for a time choked my voice and made me speechless. We both, however, got the better of our feelings and conversed freely about the past.

Though broken by age and palsy, the mind of Captain Auld was remarkably clear and strong. After he had become composed I asked him what he thought of my conduct in running away and going to the North. He hesitated a moment as if to properly formulate his reply, and said: “Frederick, I always knew you were too smart to be a slave, and had I been in your place I should have done as you did.” I said, “Captain Auld, I am glad to hear you say this. I did not run away from YOU, but from SLAVERY; it was not that I loved Caesar less, but Rome more.” I told him that I had made a mistake in my narrative, a copy of which I had sent him, in attributing to him ungrateful and cruel treatment of my grandmother; that I had done so on the supposition that in the division of the property of my old master, Mr. Aaron Anthony, my grandmother had fallen to him, and that he had left her in her old age, when she could be no longer of service to him, to pick up her living in solitude with none to help her; or in other words, had turned her out to die like an old horse. “Ah,” said he, “that was a mistake; I never owned your grandmother; she, in the division of the slaves, was awarded to my brother-in-law, Andrew Anthony; but, ” he added quickly, “I brought her down here and took care of her as long as she lived.” The fact is, that after writing my narrative, describing the condition of my grandmother, Captain Auld’s attention being thus called to it, he rescued her from destitution. I told him that this mistake of mine was corrected as soon as I discovered it, and that I had at no time any wish to do him injustice, and that I regarded both of us as victims of a system. “Oh, I never liked slavery,” he said, “and I meant to emancipate all my slaves when they reached the age of twenty-five years.” I told him I had always been curious to know how old I was, that it had been a serious trouble to me not to know when was my birthday. He said he could not tell me that, but he thought I was born in February, 1818. This date made me one year younger than I had supposed myself, from what was told me by Mistress Lucretia, Captain Auld’s former wife, when I left Lloyd’s for Baltimore in the spring of 1825; she having then said that I was eight, going on nine. I know that it was in the year 1825 that I went to Baltimore, because it was in that year that Mr. James Beacham built a large frigate at the foot of Alliceana street, for one of the South American governments. Judging from this, and from certain events which transpired at Colonel Lloyd’s, such as a boy without any knowledge of books under eight years old would hardly take cognizance of, I am led to believe that Mrs. Lucretia was nearer right as to my age than her husband.

Before I left his bedside, Captain Auld spoke with a cheerful confidence of the great change that awaited him, and felt himself about to depart in peace. Seeing his extreme weakness I did not protract my visit. The whole interview did not last more than twenty minutes, and we parted to meet no more. His death was soon after announced in the papers, and the fact that he had once owned me as a slave was cited as rendering that event noteworthy.

His life has been marked by a purity of purpose from its beginning. He has filled many offices of trust, yet in not one position has he ever betrayed his trust. He has been largely, deeply engaged in politics, yet has been no politician. That is, he understood and practiced none of the tricks of politicians. His work has always been honest and conscientious, because he believed in whatever cause he worked for, and did not, as most of our public men, have an eye to a personal reward. All the recompense he sought was a consciousness of having accomplished some good. Whatever has been given him in the way of office has been unsolicited by him. Some of our public men have wavered in their fidelity to the Republican party, when after long waiting they fail to see a substantial reward laid at their feet; but not so with Mr. Douglass. He believed implicitly in the Republican party and realized that being composed of human beings it might sometimes err; but he would say, “The Republican party is the deck and all outside is the sea.” Another saying of his is, “I would rather be with the Republican party in defeat, than with the Democratic party in victory.” By such expressions may be seen his faithful adherence to what he believed to be right.

He is generous and forgiving, almost to a fault. On the friendliest terms with Lincoln, Grant, Sumner and many of their compeers, his opinions on public matters were always heard with deference and often adopted. His clear, forcible, yet persuasive way of presenting facts, always carry conviction with it.

And now, after a long and well fought battle of seventy years, we find him still erect and strong, bearing gracefully and unassumingly the laurels he has so nobly won. No one who visits him in his beautiful home at Cedar Cottage comes away without being richer by some gem of thought, dropped by the genial host.

A few years ago Fred Douglass married a white lady, who was a clerk in his office while recorder of deeds. This was much objected to by many of his race, but on mature reflection, it has been about decided that he was no slave to take a wife as in slave times on a plantation – according to some master’s wish – but that it was his own business, and he was only responsible to God. He has been invited to the President’s levees and he and his wife shown every mark of consideration. His travel in foreign countries has in no way been embarrassed by this act. If any one thought he was so foolish as to not know what would be said of his marriage, they have mistaken the man. But Douglass did as he thought was right as he understood it. It showed he had the courage to brave popular opinion as he had done on other occasions.

Frederick Douglass enjoys a joke as well as any man I know. I was traveling with him recently from Atlantic City, New Jersey, to Washington, District of Columbia. We had been traveling on the territory of Maryland. Near Harve de Grace, a rather officious white gentleman was particularly attentive to Mr. Douglass, and after introducing himself to the eminent orator stood up and called out to the people in the car: “Gentlemen and ladies, this is Frederick Douglass, the greatest colored man in the United States.” The people flocked around him for an introduction. One white gentleman who was a Marylander, said “Let me see, Mr. Douglass, you ran away from Maryland, did you not, somewhere in this neighborhood, I believe?” “No,” said Mr. Douglass, with that grand air and good humored laugh which is his own property, “Oh, no sir, I did not run away from Maryland, I ran away from slavery.”

There are three great orators in this country, Frederick Douglass, John M. Langston and George W. Williams, the first two are a couplet of as magnificent speakers as ever heard on an American platform; the last is a gifted star ascending the zenith. Douglass and Langston are ripe with age and mellow with experience. The young man is now vigorous and full of strength and handles the less exciting subjects of the day. The older men had the subjects of slavery and reconstruction; two greater themes, can and may never engage our minds in this broad land of swift passing events. They showed their zeal and inspiration against wrong; Williams shows his learning, research, and brilliant oratory.

God grant, when in the course of nature the mantle shall fall from his shoulders, that one may spring up to wear it, to guard it as vigilantly as he has, and as lovingly and carefully protect its folds from pollution.

If the extracts here given should be long, let it be remembered that Mr. Douglass, by length of service, by preeminence in public office, by his standing not only in America, but in the world, is entitled to large space. I want the young people also to declaim these extracts. I am tired of hearing every man’s good works repeated and no Negro’s eloquence chain an audience when, too, there are such elegant specimens.

The following is taken from his great speech in the National Convention of Colored Men held in Louisville, Kentucky, September 25, 1883.

The speaker addressed the greater part of his remarks to the white citizens of the country in the nature of a rebuke for their shortcomings towards the colored race, and said:

Born on American soil, in common with yourselves, deriving our bodies and our minds from its dust; centuries having been passed away since our ancestors were torn from the shores of Africa, we, like yourselves, hold ourselves to be in every sense Americans. Having watered your soil with our tears, enriched it with our blood, performed its roughest labor in time of peace, defended it against enemies in time of war, and having at all times been loyal and true to its highest interests, we deem it no arrogance or presumption to manifest now a common concern with you for its welfare, prosperity, honor and glory.

WHAT THE NEGROES WANT.

Referring to the antagonism experienced in calling the convention, he said:

From the day the call for this convention went forth, the seeming incongruity and contradiction of holding it has been brought to our attention. From one quarter and another, sometimes with argument and sometimes without argument; sometimes with seeming pity for our ignorance, and at other times with fierce censure for our depravity, these questions have met us. With apparent surprise, astonishment and impatience, we have been asked: “What more do the colored people of this country want than they now have, and what more is possible for them?” It is said they were once slaves, they are now free; they were once subjects, they are now sovereigns; they were once outside of all American institutions, they are now inside of all, and a recognized part of the whole American people. Why, then, do they hold colored national conventions, and thus insist upon keeping up the color line between themselves and their white fellow-countrymen?”

Mr. Douglass then proceeded to answer these questions categorically, and took occasion to administer a basting to those of his people who were too mean, servile and cowardly to assert the true dignity of their manhood and their race, and referred the existence of such creatures to the lingering remains of slave caste and oppression.

To the question “Why are we here in this National Convention?” he answered:

Because the voice of a whole people, oppressed by a common injustice, is far more likely to command attention and exert an influence on the public mind than the voice of simple individuals and isolated organizations: because we may thus have a more comprehensive knowledge of the general situation and conceive more clearly and express more fully and wisely the policy it may be necessary for them to pursue. If held for good cause, and by wise, sober and earnest men, the results will be salutary. The objection to a “colored” convention lies more in sound than substance. No reasonable man will ever object to white men holding conventions in their own interest when they are once in our condition and we in theirs: when they are the oppressed and we the oppressors.

In point of fact, however, white men are already in convention against us in various ways, and at many important points; and the practical structure of American life is in convention against us. Human law may know no distinction between men in respect of rights, but human practice may. Examples are painfully abundant. The border men hate the Indians; the Californian, the Chinaman; the Mohametan, the Christian, and vice versa, and in spite of a common nature and the equality framed into law, this hate works injustice, of which each in their own name and under their own color may complain.

The apology for observing the color line in the composition of our State and National conventions is in its necessity, and because we must do this or nothing.

CIVIL RIGHTS OBSTRUCTIONS.

In vindication of the convention and its cause, the speaker continued:

It is our lot to live among a people whose laws, traditions and prejudices have been against us for centuries, and from these they are not yet free. To assume that they are free from these evils, simply because they have changed their laws, is to assume what is utterly unreasonable and contrary to facts. Large bodies move slowly; individuals may be converted on the instant and change the whole course of life; nations never.

Not even the character of a great political organization can be changed by a new platform. It will be the same old snake, though in a new skin. Though we have had war, reconstruction and abolition as a nation, we still linger in the shadow and blight of an extinct institution.

Though the colored man is no longer subject to barter and sale, he is surrounded by an adverse settlement which fetters all his movements. In his downward course he meets with no resistance, but his course upward is resented and resisted at every step of his progress. If he comes in ignorance, rags and wretchedness, he conforms to the popular belief of his character, and in that character he is welcome; but if he shall come as a gentleman, a scholar and a statesman, he is hailed as a contradiction to the national faith concerning his race, and his coming is resented as impudence. In the one case he may provoke contempt and derision, but in the other he is an affront to pride and provokes malice. Let him do what he will, there is at present no escape for him. The color line meets him everywhere, and in a measure, shuts him out from all respectable and profitable trades and callings. In spite of all your religion and laws, he is a rejected man. Not even our churches, whose members profess to follow the despised Nazarine, whose home when on earth was among the lowly and despised, have yet conquered the feeling of color madness; and what is true of our churches is also true of our courts of law. Neither is free from this all-pervading atmosphere of color hate. The one describes the Deity as impartial and “no respecter of persons,” and the other shows the Goddess of Justice as blindfolded, with a sword by her side and scales in her hand held evenly balanced between high and low, rich and poor, white and black, but both are images of American imagination, rather than of American practice. Taking advantage of the general disposition in this country to impute crime to color, white men color their faces to commit crime, and wash off the hated color to escape punishment.

Speaking of lynch law for the black man, he says:

A man accused, surprised, frightened and captured by a motley crowd, dragged with a rope around his neck in midnight darkness to the nearest tree, and told in terms of coarsest profanity to prepare for death, would be more than human if he did not in his terror-stricken appearance more confirm the suspicion of his guilt than the contrary. Worse still; in the presence of such hell-black outrages the pulpit is usually dumb, and the press in the neighborhood is silent, or openly takes sides with the mob. There are occasional cases in which white men are lynched, but one swallow does not make a summer. Every one knows that what is called lynch law is peculiarly the law for colored people and for nobody else.

He next referred to the continuation of Ku-klux outrages, and said generally this condition of things is too flagrant and notorious to require specification of proof. “Thus in all the relations of life and death we are met by the color line. We cannot ignore it if we would, and ought not if we could. It hunts us at midnight, it denies us accommodation in hotels and justice in the courts; excludes our children from schools; refuses our sons the chance to learn trades, and compels us to pursue such labor as will bring us the least reward. While we recognize the color line as a hurtful force – a mountain barrier to our progress, wounding our bleeding feet with its flinty rocks at every step – we do not despair. We are a hopeful people. This convention is a proof of our faith in you, in reason, in truth and justice, and of our belief that prejudice, with all its malign accompaniments, may yet be removed by peaceful means. When this shall come, the color line will only be used as it should be, to distinguish one variety of the human family from another.”

THE REPUBLICAN PARTY’S ATTITUDE.

Our meeting here was opposed by some of our number, because it would disturb the peace of the Republican party. The suggestion came from coward lips and misapprehends the character of that party. If the Republican party cannot stand a demand for justice and fair play, it ought to go down. We were men before that party was born, and our manhood is more sacred than any party can be. Parties were made for men, not men for parties. This hat (pointing to his big white sombrero lying on the table before him), was made for my head; not my head for the hat. (Applause.) If the six million of colored people in this country, armed with the Constitution of the United States, with a million votes of their own to lean upon, and millions of white men at their backs whose hearts are responsive to the claims of humanity, have not sufficient spirit and wisdom to organize and combine to defend themselves from outrage, discrimination and oppression, it will be idle for them to expect that the Republican party or any other political party will organize and combine for them, or care what becomes of them.

The following is taken from an anti-slavery speech delivered many years ago:

A PERTINENT QUESTION.

BY FREDERICK DOUGLASS.

Is it not astonishing that while we are plowing, planting, and reaping, using all kinds of mechanical tools, erecting houses and constructing bridges, building ships, working in metals of brass, iron and copper, silver and gold; that while we are reading, writing and ciphering, acting as clerks, merchants and secretaries, having among us lawyers, doctors, ministers, poets, authors, editors, orators and teachers; that while we are engaged in all manner of enterprises common to other men, digging gold in California, capturing the whale in the Pacific, breeding cattle and sheep on the hillside; living, moving, acting, thinking, planning; living in families as husbands, wives and children; and, above all, confessing and worshipping the Christian’s God, and looking hopefully for immortal life beyond the grave; is it not astonishing, I say, that we are called upon to prove that we are men?

In the Negro, a monthly magazine, published in Boston, Massachusetts, of date August, 1886, under the head of “MISNOMER”

Mr. Douglass wrote as follows:

Allow me to say that what is called the Negro problem seems to me a misnomer. The real problem which this nation has to solve, and the solution of which it will have to answer for in history, were better described as the white man’s problem. Here, as elsewhere, the greater includes the less. What is called the Negro problem is swallowed up by the Caucasian problem. The question is whether the white man can ever be elevated to that plane of justice, humanity and Christian civilization which will permit Negroes, Indians and Chinamen, and other dark colored races to enjoy an equal chance in the race of life. It is not so much whether these races can be made Christians as whether white people can be made Christians. The Negro is few, the white man is many. The Negro is weak, the white man is strong. In the problem of the Negro’s future, the white man is therefore the chief factor. He is the potter; the Negro is the clay. It is for him to say whether the Negro shall become a well rounded, symmetrical man, or be cramped, deformed and dwarfed. A plant deprived of warmth, moisture and sunlight cannot live and grow. And a people deprived of the means of an honest livelihood must wither and die. All I ask for the Negro is fair play. Give him this, and I have no fear for his future. The great mass of the colored people in this country are now, and must continue to be in, the South; and there, if anywhere, they must survive or perish.

It is idle to suppose these people can make any large degree of progress in morals, religion and material conditions, while their persons are unprotected, their rights unsecured, their labor defrauded, and they are kept only a little beyond the starving point.

Of course I rejoice that efforts are being made by benevolent and Christian people at the North in the interest of religion and education; but I cannot conceal from myself that much of this must seem a mockery and a delusion to the colored people there, while they are left at the mercy of anarchy and lawless violence. It is something to give the Negro religion (he could have that in time of slavery): it is more to give him the ballot. It is something to tell him that there is a place for him in the Christian’s heaven; it is more to allow him a peaceful dwelling place in this Christian country.

FREDERICK DOUGLASS.

TO BE CONTINUED: UP NEXT, MEET

W. B. DERRICK